Content Credentials That Label AI-Generated Images Are Coming To Mobile Phones And Cameras

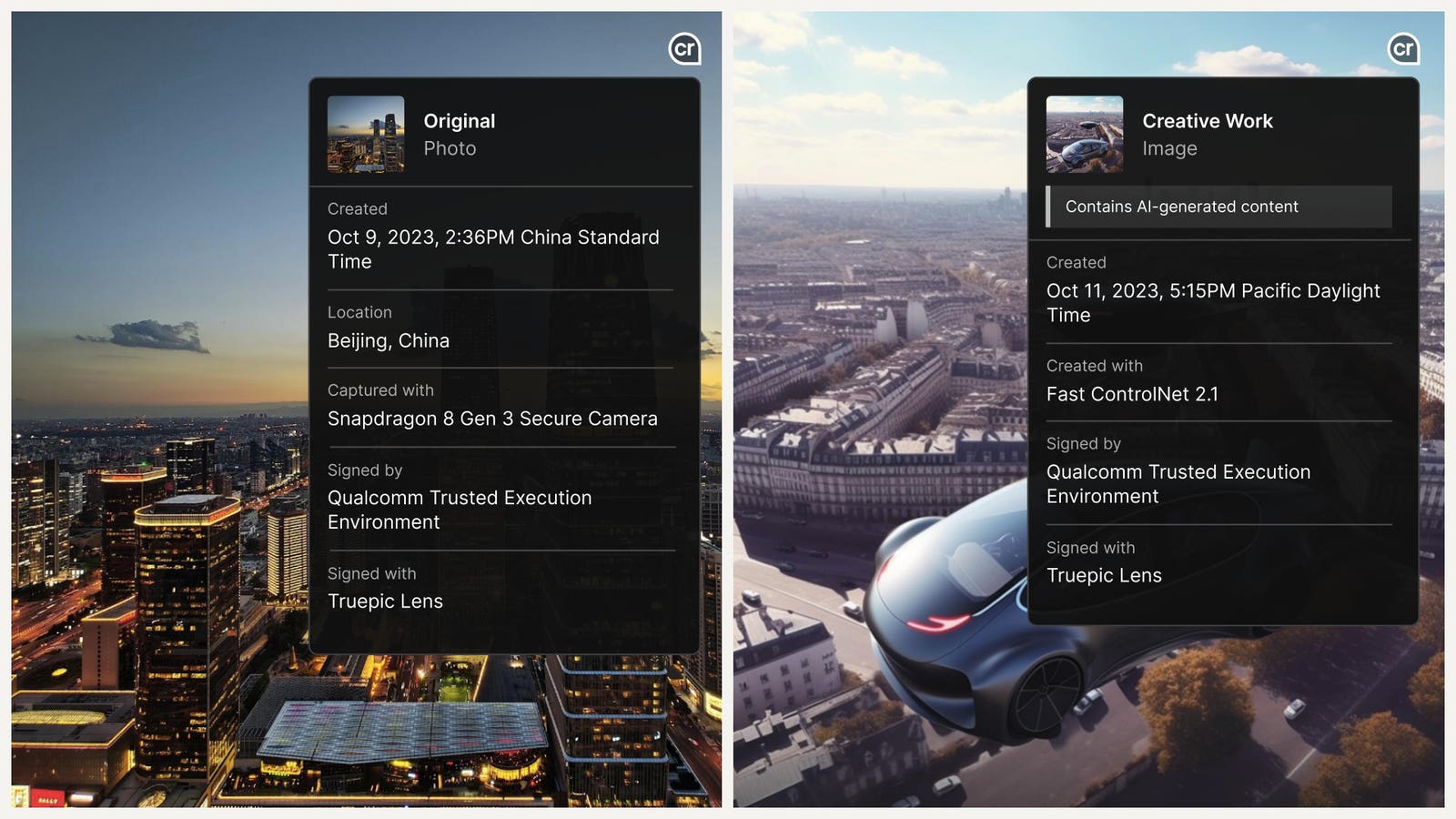

The new technology will let smartphones insert an image’s provenance data — such as time, location and the camera app used to create the image — at the hardware level, which could help people identify real and fake images.

Truepic and Qualcomm

Chip giant Qualcomm and camera manufacturer Leica have announced new technology programmed into their latest hardware that can classify images as real or synthetic.

With AI-generated content bubbling up across the internet, companies and people are grappling with ways to differentiate between what’s real and what’s not. Digital watermarks can be helpful here, but they’re easily removed and AI detection tools are not always accurate.

Now, multiple companies are starting to roll out technology that would enable devices like smartphones to insert unalterable, cryptographic provenance data — information about how, when and where a piece of content originated — into the images they create. This metadata, which would be difficult to tamper with because they’re stored at the hardware level, is designed to make it easier for people to confirm if something is real or AI-generated.

According to Qualcomm’s VP of camera Judd Heape, this is the most “foolproof,” scalable and secure way to differentiate between real and fake images. That’s why Qualcomm announced this week that smartphones like Samsung, Xiaomi, OnePlus and Motorola that use its latest chipset, the Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 Mobile Platform, can embed what is called “content credentials” into an image the moment it is created.

Similarly, German camera manufacturer Leica announced this week that its new camera will digitally stamp every photo with similar credentials —the name of the photographer, the time and place a photo was captured.

Both announcements are part of a larger industry-wide effort called the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), an alliance between Adobe, Arm, Intel, Microsoft and Truepic to develop global technical standards for certifying the originality and history of media content. Andrew Jenks, the chairman of C2PA, said that while enabling hardware to insert metadata into images isn’t a perfect solution to identifying AI-generated content, it’s more secure than watermarking, which is “brittle.”

“As long as the file remains whole, the metadata is there. If you start editing the file, the metadata may be stripped and removed. But it’s kind of the best we’ve got right now,” Jenks said. “The question is what approaches do we layer together so that we get a relatively robust response to misinformation and disinformation.”

Qualcomm’s new chipset will use technology developed by Truepic, a C2PA partner startup whose tools are used by banks and insurance providers to verify content. The technology uses cryptography to encode an image’s metadata — such as time, location and the camera app — and bind it to each pixel. If the image was made using an AI model, the technology similarly encodes which model and prompt was used to generate it. As the file travels across the internet and is edited or modified using AI or another technology, the changes are appended within the metadata in the form of a digitally signed “claim,” similar to how a document is digitally signed. If the image is edited on a machine that doesn’t comply with C2PA’s content credentials, the edit will still be included in the metadata but as an “unsigned” or an “unknown” edit.

By embedding real images with metadata that proves where they come from, the hope is that will make it easier for people who see those images circulating on the internet to trust that they are real — or know immediately they are fake.

Several image-creation apps like Adobe’s generative AI tool Firefly and Bing’s image creator already label images with content credentials, but they can be stripped or lost while exporting the file. But Truepic’s technology creates metadata that will be stored in the most secure part of Qualcomm’s chip, where critical data like credit card information and facial recognition information is also kept, so that it can’t be tampered with, Heape said.

Truepic CEO Jeffrey McGregor said the startup has focused on proving what’s real rather than detecting what is fake — what he calls a more “proactive” and “preventive” approach —because detection techniques that attempt to identify what is fake end up in an endless “cat and mouse game.” That’s because AI tools are advancing at a faster rate than detection tactics, which rely on discrepancies in AI-generated content. Newer, more powerful versions of AI models could create artificial images more immune to technological attempts at detection.

“In the long run, there’s going to be far more investment into the generative side of artificial intelligence and quality is going to quickly outstrip the pace of the detectors’ ability to accurately detect,” he said.

McGregor believes that using smartphone chips to ensure that images are embedded with information about their origins will scale, he said. But, there’s a setback in implementing this method: smartphone manufacturers and application builders must opt in to using it. Qualcomm’s Heape said convincing them to do so is a priority.

“We’re making the barrier to entry very low because this will be running directly on the Qualcomm hardware. So we can enable them right away,” he said.

Another challenge: Some applications may not support this newer type of metadata. Qualcomm’s Heape said he hopes that eventually all devices’ hardware and third-party applications will support C2PA’s content credentials. “I want to live in a world where every smartphone device, whether it’s Qualcomm or otherwise, is adopting the same standard,” he said.